As scientists, we often look at humans and nature as though they are ‘systems‘. Our descriptions of what we observe are mechanistic: formal, mathematical and algorithmical. We don’t want to invoke concepts, very familiar in other endeavours, that we cannot observe and do not have evidence for, but I expect many of us are not entirely happy seeing ourselves, our friends and family, and the natural world, in purely mechanistic terms.

So, what is something if it is not a machine?

It is easy to confuse the fact that something can be described in mechanistic terms with the belief that the thing being described is a machine. So, just because my digestion, circulatory system, immune system, lymphatic system, musculoskeletal system, nervous system, etc. etc. can be described in purely mechanistic language as the function of interactions among cells, molecules, organs, bones and skin; and even though some of these things can be replaced by actual human-made machines (e.g. heart, kidney, artificial limbs) — I am not ‘just’ a machine. To describe me, you, anyone, and indeed the rest of nature itself, as a machine is, at an emotional level, not doing any of us justice.

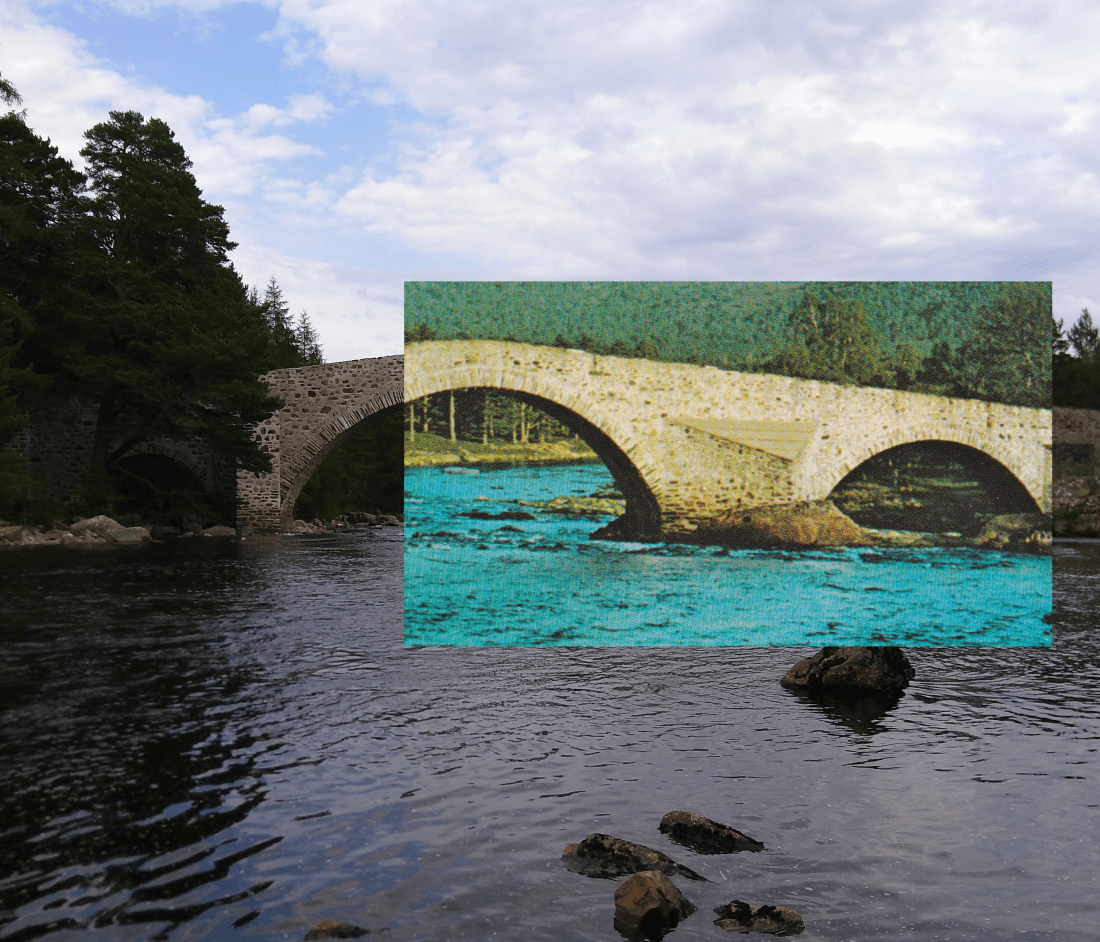

How can I assert that I am not a machine without invoking the supernatural? Well, one way of handling that kind of argument is to muck around with the definition. I don’t think I need to do that too much, however (see the screen grab above), if I say that I think a machine is necessarily something that has been designed to perform a particular function. If that’s a reasonable definition, then, as it implies, all machines must have a designer. This messes with the brain a little: describing things as machines, something scientists do to avoid invoking the supernatural, fails precisely because so doing means there must be an intentional designer of some sort (intelligent or otherwise) who needs that function performed. I think it’s a bit weak to say we’ve been ‘designed’ by nature — then we might ask who (or what) designed nature. Besides, nature doesn’t ‘need’ the functions performed by humans — looking at various environmental disasters humans have caused (more than just recently), I often wonder whether, if Nature did have intentionality, she would consider herself better off without us. Be that as it may, it is funny to watch documentaries about biology and ecology and count the number of times the word ‘design’ is used by the narrator or presenter.

If you think about it, the absence of a designer who has a function or purpose for us that we must fulfil is liberating. When I first thought of this, I was somewhat unnerved. I had a Christian upbringing. The absence of any purpose felt worrisome, perhaps because it left responsibility for what I did, and did not, do squarely on my shoulders; rather than allowing myself to duck the responsibility and claim I am just fulfilling a deity’s plan for me (or following my genetic programming, or some hapless victim of my environment). Of course, it also meant I am insignificant — there isn’t a supreme ultimate being that is deeply interested in what I do. Many schools of thought end up ascribing some sort of purpose to our lives. Besides being ‘saved’ or becoming enlightened, or whatever your religion gives as your purpose, biologists tell you you must reproduce, capitalists that you must accumulate wealth, Marxists that you must be socially ‘active’, academics that you must learn things, … How incredibly freeing it is not to have to do all those things!

There is no function or purpose we are ‘intended’ to fulfil, no plan, no destiny, no fate. This, however, does not mean we are inanimate; it does not mean we do not ‘do’ things. The things we do cause changes in the environments we inhabit. These changes can be exploited by ourselves, and by other organisms (especially if they are repeated regularly or at least partially predictably); indeed, many of the changes we cause arise from actions that themselves exploit actions by other organisms. We are part of a vast nexus of interactions, a network of life itself that is able to perpetuate itself without intention, consciousness, direction or purpose. It happens because it happens. It seems like fate, it seems like order, because we only have cognitive machinery to recognize patterns, and language to articulate that regularity. But this network is never at equilibrium, it is permanently changing, adapting, co-adapting. Niches and species emerge and disappear as life evolves.

But if we are not machines, what are we? To some extent, the very fact that this question needs to be asked is an expression of the degree to which we have lost any sense of what we are. To describe us as machines is to see us only in terms of some Platonic ideal human, and our differences from that ideal as deformity or malfunction. Instead of which, we are all unique – most of us are genetically unique; those who are not have slightly different experiences of the world that can change their body chemistry, and even the genes they pass on to their offspring. Biologically (and perhaps epistemologically depending on what you think is important about your identity), all that matters is that we can limp along for long enough to participate in the creation of the next generation. Evolution is a constant process of deformity – we are all ultimately deformed single cells. If there is no function, how can there be malfunction? This is not to say there is no suffering, no disease – quite clearly there are patterns of existence where individuals suffer. Sometimes there are interventions we can make that stop the suffering, sometimes there aren’t. But these interventions are not necessarily about restoring our bodies to some Platonic ideal – instead they are focused on stopping suffering.

There is no blueprint for you, or for me. Even your genes (sometimes metaphorically referred to as your blueprint) are not enough information to replicate you — your experiences of life may have made epigenetic switches turn off or on, and have certainly shaped the neurones in your brain. Instead, we are emergent self-organised systems. We are emergent in that we are the products of millions of years of evolution and co-evolution. We are self-organised in that there is no design for the way we work, and each of us works in individual ways (albeit with significant areas of commonality with other humans, and indeed with other species). We are systems in that the way we work can be described mechanistically. But, if even your twin does not do exactly the same thing as you, how can you be replaced by a machine? We’ve all heard that every snowflake is different, and how we are all different, and how that makes us uniquely precious. In a sense that is true, but not in any way that makes any one of us more special or precious than anyone else. The truth of that statement, however, reflects the importance of seeing ourselves, and the life around us, as more than machines.